CSE 230: Principles of Programming Languages CSE 230

Resources - Assignments - Schedule - Grading - Policies

Summary

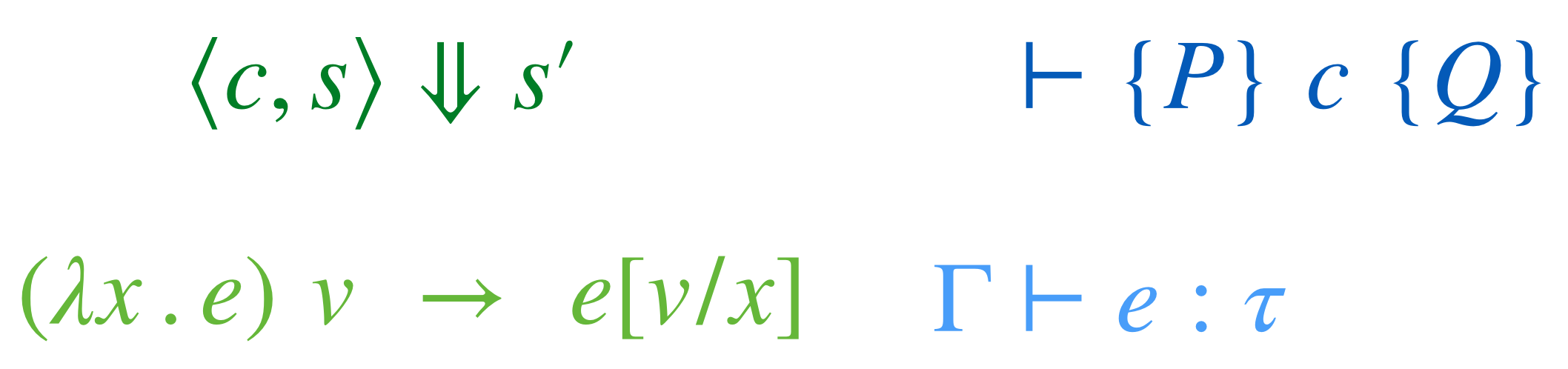

CSE 230 is an introduction to the Semantics of Programming Languages. Unlike most engineering artifacts, programming languages and hence, programs are mathematical objects whose properties can be formalized. The goal of CSE 230 is to to introduce you to the fundamental mental and mechanical tools required to rigorously analyze languages and programs and to expose you to recent developments in and applications of these techniques/

We shall study operational and axiomatic semantics, two different ways of precisely capturing the meaning of programs by characterizing their executions.

We will see how the lambda calculus can be used to distill essence of computation into a few powerful constructs.

We use that as a launching pad to study expressive type systems useful for for analyzing the behavior of programs at compile-time.

We will study all of the above in the context of lean, an interactive proof assistant that will help us precisely formalize and verify our intuitions about languages and their semantics.

Students will be evaluated on the basis of 4-6 programming (proving!) assignments, and a final exam.

Prerequisites

Basic functional programming e.g. as taught in UCSD CSE 130 using languages like Haskell, OCaml, Scala, Rust, and undergraduate level discrete mathematics, i.e. logic, sets, relations.

Basics

- Lecture: WLH 2005 TuTh 12:30p-1:50p

- Final Exam: 03/18/2025 Tu 11:30a-2:29p

- Podcasts: podcast.ucsd.edu

- Piazza: Piazza

Staff and Office Hours

- Ranjit Jhala: Tu, Th 2-3p (3110)

- Nico Lehmann: Th 3:30pm-5:00pm (Zoom), Fr 9:30am-11am (B240A), Zoom link in canvas

- Naomi Smith: Tu 12pm-3pm (Zoom)

- Matt Kolosick: Mo 10am-12pm (Zoom), Thursday 10am-11am (Zoom)

- Mingyao Shen: We 12-1p (B240A)

- Kyle Thompson: Mo 1-2p (B260A)

Please check the CANVAS calendar before you come in case there have been any changes.

Resources

The course is loosely based on Concrete Semantics but there is no official textbook; we will link to any relevant resources that may be needed to supplement the lecture material.

Some other useful links are:

- Lean

- Theorem Proving in Lean4

- Concrete Semantics

- Software Foundations

- Hitchhikers Guide to Logical Verification

- PL Foundations in Agda

Assignments

- Assignment X - Github/ID due 1/17

- Assignment 0 - Induction due 1/22

Schedule

The schedule below outlines topics, due dates, and links to assignments. The schedule of lecture topics might change slightly, but I post a general plan so you can know roughly where we are headed.

Week 1 - Basics and Induction

Week 2 - Expressions and Evidence

- Recursion and Induction

- Handout 1-14

- Compiling Expressions to Stack Machines (Ch03)

Week 3 - Big Step Semantics

- Induction on Evidence (Ch04)

- Imperative Programs: States, Commands, Transitions

- Program Equivalence (Ch07)

Week 4 - Small Step Semantics

- Preservation and Progress (Ch09)

Week 5, 6 - Axiomatic Semantics

- Assertions, Floyd-Hoare Logic, Soundness (Ch12)

- Verification Conditions and Automatic Verification

Week 7, 8 - Simply Typed Lambda Calculus

- Terms, Types, and Typing Rules

- Denotational Semantics and Type Soundness

Week 9, 10 - Automated Verification

- Satisfiability Modulo Theories

- Flux: Refinement Type based verification for Rust

Grading

Your grade will be calculated from assignments, exam, and participation

-

Participation Quizzes (15%) Most lectures will come with a 1-2 page handout, and you can submit the handout any time up until the start of the next lecture. Credit is given for reasonable effort in engaging with the material from the day on the handout.

-

Programming Assignments (40%) There will be a total of 5-6 programming assigments, to be done in pairs but submitted individually.

-

In Class Exams (45%) We will have three "in-class exams" Th 1/30 and Tu 2/25 and Th 3/13 each worth 15% of the grade.

Comprehensive Exam: For graduate students using this course for a comprehensive exam requirement, you must get "A" achievement on the exams.

Policies

All assignments are Closed collaboration assignments, where you cannot collaborate with others (except your partner). Of course you can ask questions on Piazza, and come to office hours etc. In particular,

- You cannot look at or use anyone else's code for the assignment

- You cannot discuss the assignment with other students

- You cannot post publicly about the assignment on the course message board (or on social media or other forums). Of course, you can still post questions about material from lecture or past assignments!

You should be familiar with the UCSD guidelines on academic integrity as well.

Late Work

You have a total of six late days that you can use throughout the quarter, but no more than four late days per assignment.

- A late day means anything between 1 second and 23 hours 59 minutes and 59 seconds past a deadline

- If you submit past the late day limit, you get 0 points for that assignment

- There is no penalty for submitting late but within the limit

Regrades

Mistakes occur in grading. Once grades are posted for an assignment, we will allow a short period for you to request a fix (announced along with grade release). If you don't make a request in the given period, the grade you were initially given is final.

Laptop/Device Policy in Lecture

There are lots of great reasons to have a laptop, tablet, or phone open during class. You might be taking notes, getting a photo of an important moment on the board, trying out a program that we're developing together, and so on. The main issue with screens and technology in the classroom isn't your own distraction (which is your responsibility to manage), it's the distraction of other students. Anyone sitting behind you cannot help but have your screen in their field of view. Having distracting content on your screen can really harm their learning experience.

With this in mind, the device policy for the course is that if you have a screen open, you either:

- Have only content onscreen that's directly related to the current lecture.

- Have unrelated content open and sit in one of the back two rows of the room to mitigate the effects on other students. I may remind you of this policy if I notice you not following it in class. Note that I really don't mind if you want to sit in the back and try to multi-task in various ways while participating in lecture (I may not recommend it, but it's your time!)

Diversity and Inclusion

We are committed to fostering a learning environment for this course that supports a diversity of thoughts, perspectives and experiences, and respects your identities (including race, ethnicity, heritage, gender, sex, class, sexuality, religion, ability, age, educational background, etc.). Our goal is to create a diverse and inclusive learning environment where all students feel comfortable and can thrive.

Our instructional staff will make a concerted effort to be welcoming and inclusive to the wide diversity of students in this course. If there is a way we can make you feel more included please let one of the course staff know, either in person, via email/discussion board, or even in a note under the door. Our learning about diverse perspectives and identities is an ongoing process, and we welcome your perspectives and input.

We also expect that you, as a student in this course, will honor and respect your classmates, abiding by the UCSD Principles of Community (https://ucsd.edu/about/principles.html). Please understand that others’ backgrounds, perspectives and experiences may be different than your own, and help us to build an environment where everyone is respected and feels comfortable.

If you experience any sort of harassment or discrimination, please contact the instructor as soon as possible. If you prefer to speak with someone outside of the course, please contact the Office of Prevention of Harassment and Discrimination: https://ophd.ucsd.edu/.

Assignments

- Assignment X - Github/ID due 1/17

- Assignment 0 - Induction due 1/22

Hello, World!

Welcome to CSE 230!

Principles of Programming Languages

i.e.

Formal Semantics

i.e.

Programs as Mathematical Objects

Computation is Specified by Programming Languages

Increased dependence implies increased need for analysis

- Safety Will this code crash?

- Security Will this code broadcast my social security number?

- Performance Will this code run in the appropriate time/space constraints?

CSE 230: PL/Programs are mathematical objects

Mental and Mechanical tools to reason about programs

Rigorous specification, analysis of PL/Programs...

... and thus, computation

CSE 230: Learning Outcomes

Goal: Mechanized Formal Semantics

Intellectual and Algorithmic tools for reasoning about program behavior

Semantics

- What does a program mean?

- What does a program do?

Formal

- We will define these objects mathematically

- We will learn how to prove things about these objects

Mechanized

- We will learn to use a precise language and tools to write these proofs

Why bother with Formal Semantics?

... Won't LLMs like ChatGPT, Claude, Grok, ... write all the programs?

Why bother with Formal Semantics?

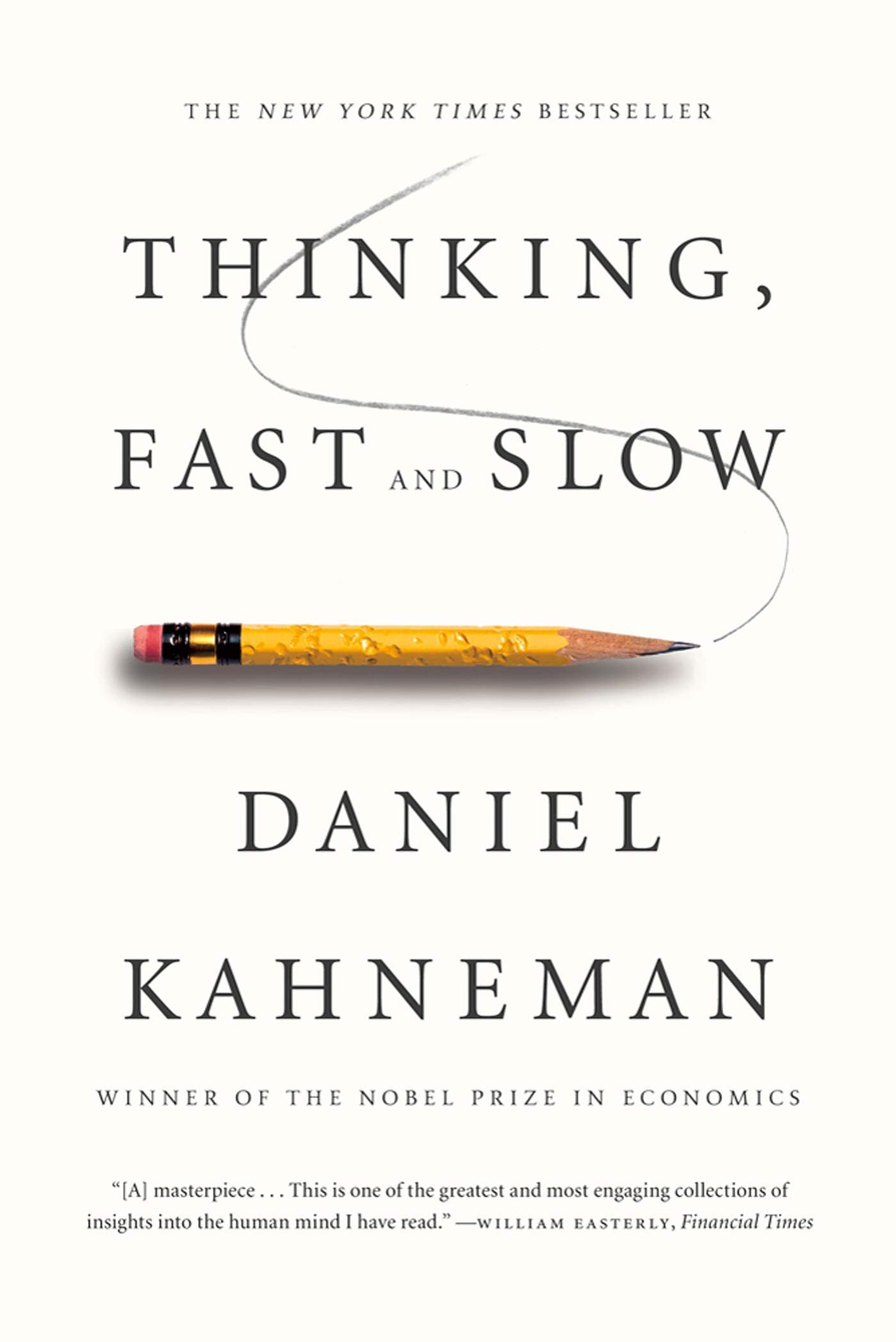

Ranjit: What is the central thesis of "thinking fast and slow"?

Via claude -- emphasis mine.

The central thesis of "Thinking, Fast and Slow" by Daniel Kahneman is that human thinking operates in two distinct systems

-

System 1 is fast, intuitive, and emotional. It operates automatically with little or no effort and no sense of voluntary control. It makes quick judgments based on familiar patterns, but is prone to systematic errors and cognitive biases.

-

System 2 is slower, more deliberative, and more logical. It allocates attention to effortful mental activities that demand it, including complex calculations and careful reasoning. While more reliable than System 1, it is lazy and often defers to System 1 unless specifically engaged.

Kahneman argues that while System 1 is remarkably capable, its biases and shortcuts (heuristics) can lead to predictable errors in judgment. Many of our decision-making problems stem from System 1 making quick judgments when slower, more analytical System 2 thinking would be more appropriate. Yet we can't simply turn off System 1 - both systems serve important functions and work together to shape our thoughts and decisions.

System 1 == LLMs vs System 2 == Formal Semantics

( H/T to Adithya Murali for the analogy... )

Why Formal Semantics in the age of LLMs?

LLMs ==> more code ==> more bugs

-

More need to really understand code!

-

More tools to help understand code!

(i.e. The more you rely on "system 1", the more you need "system 2"!)

Medium of instruction: Lean

Lean is a programming language and theorem prover

-

Used to write mathematical proofs that are automatically verified by the computer

-

Similar to many other theorem provers like Rocq (Coq), Agda, Isabelle, etc.

-

Used in academia and industry for formal verification

Two main features for CSE 230

-

Helps define and prove things about languages and programs

-

Example of state-of-the-art programming language

A quick taste of lean...

You can define functions...

def sum (n: Nat) : Nat :=

match n with

| 0 => 0 -- if n is 0, return 0

| m + 1 => m + 1 + sum m -- if n is m+1, return (m+1) + sum m

sum 5 ==> 5 + sum 4 ==> 5 + 4 + sum 3 ==> 5 + 4 + 3 + 2 + 1 + sum 0 ==> 5 + 4 + 3 + 2 + 1 + 0

You can evaluate i.e. "run" them ...

#eval sum 100

You can automatically check simple facts about them...

def i_had_soup_for_lunch : sum 100 = 5050 :=

rfl

And finally, you can write proofs for more complicated facts ...

theorem sum_eq : ∀ (n: Nat), 2 * sum n = n * (n + 1) := by

intro n

induction n

. case zero =>

rfl

. case succ =>

rename_i m ih

simp_arith [sum, ih, Nat.mul_add, Nat.mul_comm]

Logistics

Lets talk about the course logistics...

Course Outline

About 2-ish weeks per topic, roughly following Concrete Semantics by Tobias Nipkow and Gerwin Klein

Part I: Basics of Lean and Proofs

- Expressions & Types

- Datatypes & Proofs

- Recursion & Induction & Evidence

Part II: Operational Semantics

- Big Step Semantics

- Small Step Semantics

Part III: Axiomatic Semantics

- Floyd-Hoare Logic

- VC Generation and Automated Verification

Part IV: Types

- Simply Typed Lambda Calculus

- Denotational Type Soundness

Prerequisites

Basic functional programming

- e.g. as taught in UCSD CSE 130

- using languages like Scheme, Haskell, Ocaml, Scala, Rust, ...

Undergraduate level discrete mathematics,

- e.g. as taught in UCSD CSE 20

- boolean logic, quantifiers, sets, relations, ...

You may be able to take 130 if you're unfamiliar with the above but ...

Grading

Your grade will be calculated from assignments, exam, and participation

-

Handouts (15%) Most lectures will come with a 1-2 page handout, and you can submit the handout any time up until the start of the next lecture. Credit is given for reasonable effort in engaging with the material from the day on the handout.

-

Programming Assignments (40%) There will be a total of 5-6 programming assigments, to be done in pairs but submitted individually.

-

In Class Exams (45%) We will have three "in-class exams" Th 1/30 and Tu 2/25 and Th 3/13 each worth 15% of the grade.

Comprehensive Exam: For graduate students using this course for a comprehensive exam requirement, you must get "A" achievement on the exams.

Assignments (5-6)

- You can work with a partner, but submit individually

- Github Classroom + Codespaces

Assignment 0 Fill out this form to link UCSD ID and Github

And now, let the games begin...!

Expressions, Types and Functions

This material is based on sections 1-3 of Functional Programming in Lean

Expressions

In lean, programs are built from expressions which (if well-typed) have a value.

| Expression | Value |

|---|---|

1 + 2 | 3 |

3 * 4 | 12 |

1 + 2 * 3 + 4 | 11 |

Lean expressions are mathematical expressions as in Haskell, Ocaml, etc.

- variables get a "bound" to a single value (no "re-assignment"),

- expressions always evaluate to the same value ("no side effects")

- if two expressions have the same value, then replacing one with the other will not cause the program to compute a different result.

To evaluate an expression, write #eval before it in your editor,

and see the result by hovering over #eval.

#eval 1 + 2

#eval 3 * 4

#check 1 + 2 * 3 + 4

Types

Every lean expression has a type.

The type tells lean -- without evaluating the expression -- what kind of value it will produce.

Why do Programming Languages need types???

Lean has a very sophisticated type system that we will learn more about soon...

To see the type of an expression, write #check before it in your editor,

Primitive: Nat

Lean has a "primitive" type Nat for natural numbers (0, 1, 2, ...) that we saw

in the expressions above.

#check 1 -- Nat (natural number i.e. 0, 1, 2,...)

#check 1 + 2 -- Nat

QUIZ What is the value of the following expression?

#eval (5 - 10 : Int)

/-

(A) 5 0%

(B) 10 0%

(C) -5 30%

(D) 0 5%

(E) None of the above 17%

-/

Type Annotations

Sometimes lean can infer the type automatically.

But sometimes we have to (or want to) give it an annotation.

Primitive: Int

#check (1 : Int) -- Int (..., -2, -1, 0, 1, 2,...)

#check (1 + 2 : Int) -- Int

QUIZ What is the value of the following expression?

#eval (5 - 10 : Int)

Primitive: Float

#check 1.1 -- Float

#eval 1.1 + 2.2

Primitive: Bool

#eval true

#check true -- Bool

#eval false

#check false -- Bool

#eval true && true

#eval true && false

#eval false && true

#eval false && false

#eval true || true

#eval true || false

#eval false || true

#eval false || false

-- #eval false + 10 -- type error!

Primitive: String

#eval "Hello, " ++ "world!"

#check "Hello, " ++ "world!" -- String

-- #eval "Hello, " ++ 10 -- type error!

-- #eval "Hello, " ++ world -- unknown identifier!

Definitions

We can name expressions using the def keyword.

def hello := "hello"

def world := "world"

def one := 1

def two := 2

def five_plus_ten := 5 + 10

def five_minus_ten := 5 - 10

def five_minus_ten' : Int := 5 - 10

You can now #check or #eval these definitions.

#check hello

#eval hello

#eval hello ++ world

#eval five_minus_ten

#eval five_minus_ten'

Functions

In lean, functions are also expressions, as in the λ-calculus.

#check (fun (n : Nat) => n + 1) -- Nat -> Nat

#check (λ (n : Nat) => n + 1) -- Nat -> Nat

#check (fun (x y : Nat) => x + y) -- Nat -> (Nat -> Nat)

#check (λ (x y : Nat) => x + y) -- Nat -> Nat -> Nat

#check (λ (x : Nat) => λ (y: Nat) => x + y) -- Nat -> Nat -> Nat

QUIZ What is the type of the following expression?

Nat -> Nat -> Bool

#check (fun (x y : Nat) => x > y)

Function Calls

You can call a function by putting the arguments in front

#eval (fun x => x + 1) 10

#eval ((fun x y => x + y) 100) 200

/-

((fun x y => x + y) 100) 200

==

((λ x => (λ y => x + y)) 100) 200

==

(( (λ y => 100 + y))) 200

==

100 + 200

==

300

-/

QUIZ What is the value of the following expression?

#eval (fun x y => x > y) 10 20

Function Definitions

Of course, it is more convenient to name functions as well, using def

since naming allows us to reuse the function in many places.

def inc := fun (x : Int) => x + 1

def inc'(x: Int) := x + 1

#eval inc 10

#eval inc 20

-- #eval inc true -- type error!

def add := fun (x y : Nat) => x + y

def add' (x y : Nat) := x + y

#eval add 10 20

#eval add' 10 20

It is often convenient to write the parameters of the function to the left

The below definitions of inc' and add' are equivalent to the above definitions of inc and add.

def inc'' (x : Int) : Int := x + 1

#eval inc'' 10 -- 11

def add'' (x y : Nat) : Nat := x + y

#eval add'' 10 20 -- 30

EXERCISE Write a function max that takes two Nats and returns the maximum of the two.

EXERCISE Write a function max3 that takes three Nats and uses max to compute the maximum of all three

EXERCISE

Write a function joinStringsWith of type String -> String -> String -> String

that creates a new string by placing its first argument between its second and third arguments.

def mymax (x y : Nat) := if x > y then x else y

def mymax3 (x y z : Nat) := mymax x (mymax y z)

#eval mymax 67 92

-- #eval joinStringsWith ", " "this" "that" -- "this, that"

-- #check joinStringsWith ", " -- **QUIZ** What is the type of the expression on the left?

EXERCISE

Write a function volume of type Nat -> Nat -> Nat -> Nat which computes

the volume of a brick given height, width, and depth.

Datatypes and Recursion

This material is based on sections 5,6 of Functional Programming in Lean

Datatypes

So far, we saw some "primitive" or "built-in" types like Nat, Bool etc.

The "primitive" Bool type is actually defined as a datatype in the standard library:

The type has two constructors

Bool.falseBool.true.

Which you can think of as "enum"-like constructors.

Like all (decent) modern languages, Lean lets you construct

new kinds of datatypes. Let's redefine Bool locally, just to

see how it's done.

namespace MyBool

inductive Bool : Type where

| false : Bool

| true : Bool

deriving Repr

#eval Bool.true

Pattern Matching

The constructors let us produce or build values of the datatype.

The only way to get a Bool is by using the Bool.true or Bool.false constructors.

In contrast, pattern-matching lets us consume or use the values of that datatype...

Lets write a function neg that takes a Bool and returns the opposite Bool, that is

- when given

Bool.true,negshould returnBool.false - when given

Bool.false,negshould returnBool.true

def neg (b: Bool) :=

match b with

| Bool.true => Bool.false

| Bool.false => Bool.true

Lets test it to make sure the right thing is happening

#eval neg Bool.true

#eval neg Bool.false

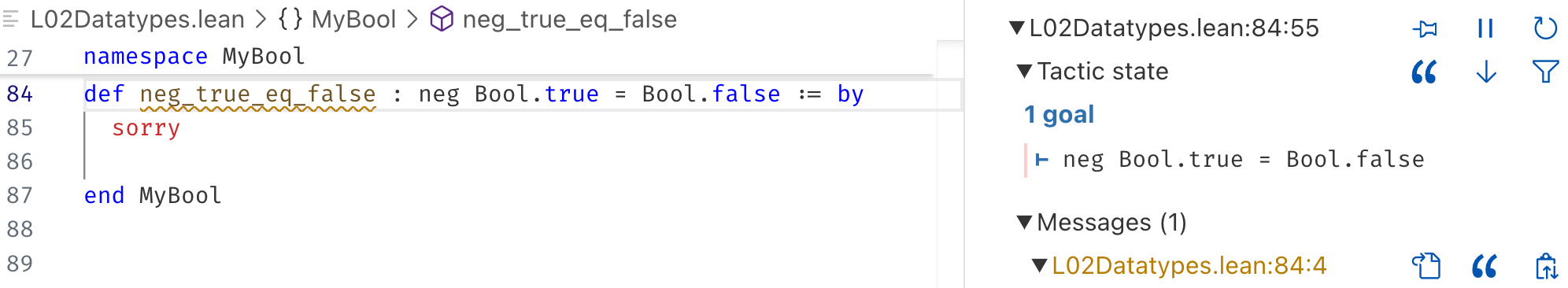

Our first "theorem" ... let us prove that neg true is false by

- defining a variable

neg_true_eq_false(you can call it whatever you like...) - whose type is the proposition

neg Bool.true = Bool.falsewe want to "prove" - whose body is the proof of the proposition.

For now, lets just write by sorry for the "proof".

def neg_b_neq : ∀ (b:Bool), ¬ (neg b = b) := by

intros b

cases b <;> simp [neg]

def neg_neg_b_eq : ∀ (b:Bool), neg (neg b) = b := by

intros b

cases b <;> simp [neg]

def neg_true_eq_false : neg Bool.true = Bool.false := by

rfl

foo <;> bar

Goals

How shall we write the proof?

Well, you can see the goal by

- putting the cursor next to the

by(beforesorry) - looking at the

Lean Infoviewon the right in vscode

A goal always looks like h1, h2, h3, ... ⊢ g where

h1,h2,h3etc. are hypotheses i.e. what we have, and<g>is the goal i.e. what we want to prove.

In this case, the hypotheses are empty and the goal is neg Bool.true = Bool.false.

Tactics

Proofs can be difficult to write (in this case, not so much).

Fortunately, lean will help us build up the proof by

- giving us the goal that

- we can gradually simplify, split ...

- till we get simple enough sub-goals that it can solve automatically.

TACTIC rfl: The most basic tactic is rfl which abbreviates

reflexivity, which is a fancy way of saying "evaluate the lhs and

rhs and check if they are equal".

EXERCISE: Write down and "prove" the theorem that neg false is true.

EXERCISE What other "facts" can you think up (and prove!) about neg?

Next, lets try to prove a fact about how neg

behaves on all Bool values. For example,

lets try to prove that when we neg a Bool

value b two times we get back b.

def neg_neg : ∀ (b: Bool), neg (neg b) = b := by

sorry

This time we cannot just use rfl -- try it and see what happens!

In its own way, lean is saying "I can't tell you (evaluate) what neg b

is because I don't know what b is!"

TACTIC intros: First, we want to use the intros tactic which will "move"

the ∀ (b: Bool) from the goal into a plain b : Bool hypothesis.

That is, the intros tactic will change the goal from

∀ (b: Bool), neg (neg b) = b to b : Bool ⊢ neg (neg b) = b,

meaning that our task is now to prove that neg (neg b) = b

assuming that b is some Bool valued thing.

Of course, we still cannot use rfl because lean does not know what

neg b until b itself has some concrete value.

TACTIC cases: The path forward in this case is to use the cases tactic

which does a case analysis on b, i.e. tells lean to split cases on each

of the possible values of b --- when it is true and when it is false.

Now, when you put your cursor next to cases b you see the two subgoals

case falsewhich is⊢ neg (neg Bool.false) = Bool.falsecase truewhich is⊢ neg (neg Bool.true) = Bool.true

Each case (subgoal) can be proved by rfl so you can complete the proof as

def neg_neg_1 : ∀ (b : Bool), neg (neg b) = b := by

intros b

cases b

rfl

rfl

However, I prefer to make the different subgoals more "explicit" by writing

def neg_neg_2 : ∀ (b : Bool), neg (neg b) = b := by

intros b

cases b

. case false => rfl

. case true => rfl

Conjunction Lets write an and function that

- takes two

Bools and - returns a

Boolthat istrueif both aretrueandfalseotherwise.

def and (b1 b2: Bool) : Bool :=

match b1, b2 with

| Bool.true, Bool.true => Bool.true

| _ , _ => Bool.false

and is Commutative Lets try to prove that and

is commutative, i.e. and b1 b2 = and b2 b1.

You can start off with intros and then use cases

as before, but we may have to do case analysis on both

the inputs!

theorem and_comm : ∀ (b1 b2 : Bool), and b1 b2 = and b2 b1 := by

sorry

TACTIC COMBINATOR <;>: It is a bit tedious to repeat the same sub-proof so many times!

The foo <;> bar tactic combinator lets you chain tactics together so by first applying foo

and then applying bar to each sub-goal generated by foo. We can use <;> to considerably

simplify the proof. In the proof below, move your mouse over the cases b1 <;> cases b2 <;> ...

line and see how the goals change in the Lean Infoview panel.

theorem and_comm' : ∀ (b1 b2 : Bool), and b1 b2 = and b2 b1 := by

-- use the <;> tactic combinator

sorry

Disjunction Lets write an or function that

- takes two

Bools and - returns a

Boolthat istrueif either istrueandfalseotherwise.

def or (b1 b2: Bool) : Bool := sorry

EXERCISE Complete the proof of the theorem that or is commutative,

i.e. or produces the same result no matter the order of the arguments.

theorem or_comm : ∀ (b1 b2 : Bool), or b1 b2 = or b2 b1 := by

sorry

end MyBool

Recursion

Bool is a rather simple type that has just two elements --- true and false.

Pretty much all proofs about Bool can be done by splitting cases on the relevant Bool

values and then running rfl (i.e. via a giant "case analysis").

Next, lets look at a more interesting type, which has an infinite number of values.

namespace MyNat

inductive Nat where

| zero : Nat

| succ : Nat -> Nat

deriving Repr

open Nat

Zero, One, Two, Three, ... infinity

Unlike Bool there are infinitely many Nat values.

def n0 : Nat := zero

def n1 : Nat := succ zero

def n2 : Nat := succ (succ zero)

def n3 : Nat := succ (succ (succ zero))

This has two related consequences.

First, we cannot write interesting functions over Nat

just by brute-force enumerating the inputs and outputs

as we did with and and or; instead we will have to

use recursion.

Second, we cannot write interesting proofs over Nat

just by brute-force case-splitting over the values

as we did with and_comm and or_comm; instead we will

have to use induction.

Addition

Lets write a function to add two Nat values.

def add (n m: Nat) : Nat :=

match n with

| zero => m

| succ n' => succ (add n' m)

example : add n1 n2 = n3 := by rfl

Adding Zero

Next, lets try to prove some simple facts about add for example

theorem add_zero_left : ∀ (n: Nat), add zero n = n := by

intros

rfl

The proof of add_zero_left is super easy because it is literally

(part of) the definition of add which tells lean that it obeys

two equations

add zero m = m

add (succ n') m = succ (add n' m)

So the rfl applies the first equation and boom we're done.

Adding Zero on the Right

However, lets see what happens if we flip the order of the arguments,

so that the second argument is zero

theorem add_zero' : ∀ (n: Nat), add n zero = n := by

intros n

sorry

Boo! Now the proof fails because the equation does not apply!

"Calculation" or "Equational Reasoning"

In fact, lets us try to see why the theorem is even true,

slowly working our way up the Nat numbers.

add zero zero

{ by def of add }

===> zero ... (0)

add (succ zero) zero

{ by def of add }

===> succ (add zero zero)

{ by (0) }

===> succ zero ... (1)

add (succ (succ (zero))) zero

{ by def }

===> succ (add (succ zero) zero)

{ by (1) }

===> succ (succ zero) ... (2)

add (succ (succ (succ (zero)))) zero

{ by def }

===> succ (add (succ (succ zero)) zero)

{ by (2) }

===> succ (succ (succ zero)) ... (3)

calc mode

lean has a neat calc mode that lets us write

the above proofs (except, they are actually checked!)

theorem add_0 : add zero zero = zero := by

calc

add zero zero = zero := by simp [add] -- just apply the

theorem add_1 : add (succ zero) zero = succ zero := by

calc

add (succ zero) zero

= succ (add zero zero) := by simp [add]

_ = succ zero := by simp [add_0]

theorem add_2 : add (succ (succ zero)) zero = succ (succ zero) := by

calc

add (succ (succ zero)) zero

= succ (add (succ zero) zero) := by simp [add]

_ = succ (succ zero) := by simp [add_1]

theorem add_3 : add (succ (succ (succ zero))) zero = succ (succ (succ zero)) := by

calc

add (succ (succ (succ zero))) zero

= succ (add (succ (succ zero)) zero) := by simp [add]

_ = succ (succ (succ zero)) := by simp [add_2]

Proof by Induction

Notice that each of the proofs above is basically the same:

To prove the fact add_{n+1} we

- apply the definition of

addand then - recursively use the fact

add_{n}!

Recursion

Lets us define add for each Nat by reusing the definitions on smaller numbers

Induction

Lets us prove add_n for each Nat by reusing the proofs on smaller numbers

theorem add_zero : ∀ (n: Nat), add n zero = n := by

intros n

induction n

. case zero => simp [add]

. case succ n' ih => simp [add, ih]

end MyNat

Polymorphism

lean also lets you define polymorphic types and functions.

For example, here is the definition of a List type that can

hold any kind of value

namespace MyList

inductive List (α : Type) where

| nil : List α

| cons : α -> List α -> List α

deriving Repr

open List

List constructors

Just like Nat has a

- "base-case" constructor (

zero) and - "inductive-case" constructor (

succ)

A List α also has two constructors:

- "base-case" constructor (

nil) and - "inductive-case" constructor (

cons)

NOTE: You can type the α by typing a \ + a

So we can create different types of lists, e.g.

def list0123 : List Int := cons 0 (cons 1 (cons 2 (cons 3 nil)))

def list3210 : List Int := cons 3 (cons 2 (cons 1 (cons 0 nil)))

def listtftf : List Bool := cons true (cons false (cons true (cons false nil)))

Appending Lists

Lets write a small function to append or concatenate two lists

To do so, we match on the cases of the first list xs

- If

xsisnilthen the result is just the second list - If

xsis of the formcons x xs'then we recursivelyapp xs' ysandcons xin front

def app {α : Type} (xs ys: List α) : List α :=

match xs with

| nil => ys

| cons x xs' => cons x (app xs' ys)

Just like with add the above definition tells lean that app satisfies two equations

- ∀ ys, app nil ys = ys

- ∀ x xs' ys, app (cons x xs') ys = cons x (app xs' ys)

example : app nil (cons 2 (cons 3 nil)) = cons 2 (cons 3 nil) := by rfl

example : app (cons 1 nil) (cons 2 (cons 3 nil)) = cons 1 (cons 2 (cons 3 nil)) := by rfl

example : app (cons 0 (cons 1 nil)) (cons 2 (cons 3 nil)) = cons 0 (cons 1 (cons 2 (cons 3 nil))) := by rfl

Digression: Implicit vs Explicit Parameters

The α -- representing the Type of the list elements --

is itself a parameter for the app function.

- The

{..}tellsleanthat it is an implicit parameter vs - The

(..)we usually use for explicit parameters

An implicit parameter, written {...} is a parameter that lean

tries to automatically infer at call-sites, based on the context, for example

def add (n : Nat) (m : Nat) : Nat := n + m

#eval add 3 4 -- Must provide both arguments: 7

An explicit parameter, written (...) is the usual kind where you

have to provide at call-sites, for example

def singleton {α : Type} (x: α) : List α := cons x nil

#eval singleton 3

Induction on Lists

app is sort of like add but for lists. For example, it is straightforward to prove

"by definition" that

theorem app_nil_left: ∀ {α : Type} (xs: List α), app nil xs = xs := by

intros

rfl

However, just like add_zero we need to use induction to prove that

theorem app_nil : ∀ {α : Type} (xs: List α), app xs nil = xs := by

sorry

Because in the cons x xs' case, we require the fact that app_nil holds

for the smaller tail xs', i.e that app xs' nil = xs', which the induction

tactic will give us as the hypothesis that we can use.

Associativity of Lists

theorem app_assoc : ∀ {α : Type} (xs ys zs: List α), app (app xs ys) zs = app xs (app ys zs) := by

sorry

end MyList

set_option pp.fieldNotation false

Datatypes and Recursion

This material is based on

- Chapter 2 of Concrete Semantics

- Induction Exercises by James Wilcox

namespace MyNat

inductive Nat where

| zero : Nat

| succ : Nat -> Nat

deriving Repr

open Nat

def add (n m : Nat) : Nat :=

match n with

| zero => m

| succ n' => succ (add n' m)

Trick 1: Helper Lemmas

Example add_comm

Let's try to prove that add is commutative; that is, that the order of arguments does not matter.

If we plunge into trying a direct proof-by-induction, we get stuck at two places.

- What is the value of

add m zero? - What is the value of

add m (succ n)?

It will be convenient to have helper lemmas that tell us that

∀ m, add m zero = m∀ n m, add n (succ m) = succ (add n m)

theorem add_comm : ∀ (n m: Nat), add n m = add m n := by

intros n m

induction n

sorry

end MyNat

open List

Example rev_rev

Lets look at another example where we will need helper lemmas.

Appending lists

def app {α : Type} (xs ys: List α) : List α :=

match xs with

| [] => ys

| x::xs' => x :: app xs' ys

/-

app [] [3,4,5] = [3,4,5]

app (2::[]) [3,4,5] = [3,4,5]

==>

2 :: [3,4,5]

==>

[2,3,4,5]

-/

example : app [] [3,4,5] = [3,4,5] := rfl

example : app [0,1,2] [3,4,5] = [0,1,2,3,4,5] := rfl

Reversing lists

def rev {α : Type} (xs: List α) : List α :=

match xs with

| [] => []

| x :: xs' => app (rev xs') [x]

example : rev [] = ([] : List Int) := rfl

example : rev [3] = [3] := rfl

example : rev [2,3] = [3,2] := rfl

example : rev [0,1,2,3] = [3,2,1,0] := rfl

example : rev (rev [0,1,2,3]) = [0,1,2,3] := rfl

rev [0,1,2,3] => rev (0 :: [1,2,3]) => app (rev [1,2,3]) [0] => app [3,2,1] [0] => [3,2,1,0]

Now, lets prove that the above was not a fluke: if you reverse a list twice then you get back the original list.

theorem rev_app : ∀ {α : Type} (xs ys : List α),

rev (app xs ys) = app (rev ys) (rev xs) := by

sorry

/-

rev (app xs ys) == app (rev ys) (rev xs)

rev (app [x1,x2,x3,...xn] [y1...ym])

== rev [x1...xn, y1...ym]

== [ym ... y1, xn ... x1]

== app [ym ... y1] [xn ... x1]

== app (rev ys) (rev xs)

-- |- rev (app (rev xs') [x]) = x :: xs'

==>

app (rev [x]) (rev (rev xs'))

-/

theorem rev_rev : ∀ {α : Type} (xs: List α), rev (rev xs) = xs := by

intros α xs

induction xs

. case nil =>

rfl

. case cons x xs' ih =>

simp [rev, rev_app, app, ih]

Yikes. We're stuck again. What helper lemmas could we need?

Trick 2: Generalizing the Variables

Consider the below variant of add.

How is it different than the original?

open MyNat.Nat

def itadd (n m: MyNat.Nat) : MyNat.Nat :=

match n with

| zero => m

| succ n' => itadd n' (succ m)

/-

itadd (s s s z) (s s s s s z)

=>

itadd (s s z) (s s s s s s z)

=>

itadd (s z) (s s s s s s s z)

=>

itadd (z) (s s s s s s s s z)

=>

(s s s s s s s s z)

-/

example : itadd (succ (succ zero)) (succ zero) = succ (succ (succ zero)):= by rfl

Lets try to prove that itadd is equivalent to add.

add n' (succ m) == succ (add n' m)

theorem add_succ : ∀ (n m), MyNat.add n (succ m) = succ (MyNat.add n m) := by

sorry

theorem itadd_eq : ∀ (n m), itadd n m = MyNat.add n m := by

intros n

induction n

. case zero => simp [itadd, MyNat.add]

. case succ n' ih =>

simp [MyNat.add, itadd, add_succ, ih]

Ugh! Why does the proof fail???

We are left with the goal

m n' : MyNat.Nat

ih : itadd n' m = MyNat.add n' m

⊢ itadd n' (succ m) = succ (MyNat.add n' m)

IH is too weak

In the goal above, the ih only talks about itadd n m but says nothing

about itadd n (succ m). In fact, the IH should be true for all values of m

as we do not really care about m in this theorem. That is, we want to tell

lean that the ih should be

m n' : MyNat.Nat

ih : ∀ m, itadd n' m = MyNat.add n' m

⊢ itadd n' (succ m) = succ (MyNat.add n' m)

Generalizing

We can do so, by using the induction n generalizing m which tells lean that

- we are doing induction on

nand - we don't care about the value of

m

Now, go and see what the ih looks like in the case succ ...

This time we can actually use the ih and so the proof works.

theorem add_succ : ∀ (n m), MyNat.add n (succ m) = succ (MyNat.add n m) := by

sorry

theorem itadd_eq' : ∀ (n m: MyNat.Nat), itadd n m = MyNat.add n m := by

intros n m

induction n generalizing m

case zero => simp [MyNat.add, itadd]

case succ => simp [MyNat.add, MyNat.add_succ, itadd, *]

Trick 3: Generalizing the Induction Hypothesis

Often, the thing you want to prove is not "inductive" by itself. Meaning, that

you want to prove a goal ∀n. P(n) but in fact you need to prove something stronger

like ∀n. P(n) /\ Q(n) or even ∀n m, Q(n, m) which then implies your goal.

Example: Tail-Recursive sum

sum 3

=>

3 + sum 2

=>

3 + 2 + sum 1

=>

3 + 2 + 1 + sum 0

=>

3 + 2 + 1 + 0

def sum (n : Nat) : Nat :=

match n with

| 0 => 0

| n' + 1 => n + sum n'

def loop (n res : Nat) : Nat :=

match n with

| 0 => res

| n' + 1 => loop n' (res + n)

def sum_tr (n: Nat) := loop n 0

-- loop (n' + 1) 0 == sum (n' + 1)

-- loop a 0 == sum a

-- loop n res == (sum n) + res

theorem loop_sum : ∀ n res, loop n res = (sum n) + res := by

intros n res

induction n generalizing res

. case zero =>

simp [loop, sum]

. case succ n' ih =>

simp_arith [loop, sum, ih]

theorem sum_eq_sum_tr : ∀ n, sum_tr n = sum n := by

simp [sum_tr, loop_sum]

/-

fn sum(mut n: Nat) -> Nat {

let mut res = 0

while let S n' = n {

res = res + n;

n = n';

}

res

}

-/

Tail-Recursively Summing

In an iterative language you might write a loop

to sum the numbers n + n-1 + ... + 0 e.g.

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { fn sum_tr(mut n: Nat) { let mut acc = 0; while let succ m = n { acc += n; n = m } return acc } }

We can write the above with tail-recursion

- The recursive call is the "last thing" the function does

- That is, the recursive result is returned without any further computation

NOTE: Go and look at itadd; is it tail recursive?

-- def sum_tr (n acc : Nat) : Nat :=

-- match n with

-- | 0 => acc

-- | n' + 1 => sum_tr n' (n + acc)

-- def sum' (n: Nat) := sum_tr n 0

Lets try to prove that sum and sum' always compute the same result.

theorem sum_eq_sum' : ∀ n, sum n = sum' n := by

intros n

induction n

sorry

Oops, we are stuck.

We need to know something about sum_tr n' (n' + 1) but what?

Can you think of a suitable helper lemma, which would let us directly

prove sum_eq_sum'?

theorem helper: ∀ n acc, sum_tr n acc = sum n + acc := by ...

theorem sum_eq_sum' : ∀ n, sum' n = sum n := by

intros

simp_arith [sum', helper]

open List

Example: Tail-Recursive sum_list

Summing a List*

def sum_list (xs : List Nat) : Nat :=

match xs with

| [] => 0

| x ::xs' => x + sum_list xs'

Tail-Recursively Summing a List*

In an iterative language you might write a loop to sum the elements of a list, e.g.

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { fn sum_list(xs: List<Nat>) { let mut acc = 0; while let cons x ys = xs { acc += x; xs = ys } return acc } }

We can write the above with tail-recursion (where the recursive call is the "last thing")

that the function does. (Hint: Go and look at itadd; is it tail recursive?)

def sum_list_tr (xs : List Nat) (acc : Nat): Nat :=

match xs with

| [] => acc

| x :: ys => sum_list_tr ys (acc + x)

def sum_list' (xs: List Nat) := sum_list_tr xs 0

Can you figure out a suitable helper lemma that would let us complete

the proof of sum_list_eq_sum_list' below?

theorem sum_list'_eq : ∀ (xs acc), sum_list_tr xs acc = sum_list xs + acc := by

sorry

theorem sum_list_eq_sum_list' : ∀ xs, sum_list' xs = sum_list xs := by

intros xs

simp_arith [sum_list', sum_list'_eq]

Example: Tail-Recursive Reverse

rev_tr [0,1,2,3]

=>

loop [0,1,2,3] []

=>

loop [1,2,3] [0]

=>

loop [2,3] [1, 0]

=>

loop [3] [2, 1, 0]

=>

loop [] [3, 2, 1, 0]

=>

[3,2,1,0]

def rev_tr {α : Type} (xs res: List α) : List α :=

match xs with

| [] => res

| x ::xs' => rev_tr xs' (x :: res)

def rev' (xs: List α) := rev_tr xs []

example : rev' [0,1,2,3] = [3,2,1,0] := by rfl

Can you figure out a suitable helper lemma rev_tr_app that would let us complete

the proof of rev_eq_rev' below?

rev_tr xs [] == rev xs

rev_tr xs res

== [xn, ...x3, x2,x1, 99]

== rev xs ++ res

theorem app_nil : ∀ {α : Type} (xs: List α), app xs [] = xs := by

sorry

theorem rev_tr_helper_theorem : ∀ {α : Type} (xs res : List α),

rev_tr xs res = app (rev xs) res := by sorry

theorem rev_eq_rev' : ∀ {α : Type} (xs: List α), rev' xs = rev xs := by

intros α xs

simp [rev', rev_tr_helper_theorem, app_nil]

Example: Tail-Recursive Evaluator

Arithmetic Expressions

inductive Aexp : Type where

| const : Nat -> Aexp

| plus : Aexp -> Aexp -> Aexp

deriving Repr

open Aexp

def two_plus_three := plus (const 2) (const 3)

alice_plus

/ \

bob_const bob_const

| |

2 3

Evaluating Expressions

def eval (e: Aexp) : Nat :=

match e with

| const n => n

| plus e1 e2 => eval e1 + eval e2

#eval eval two_plus_three

def eval_acc (e: Aexp) (res: Nat) : Nat :=

match e with

| const n => n + res

| plus e1 e2 => eval_acc e2 (eval_acc e1 res)

def eval' (e: Aexp) := eval_acc e 0

example : eval' two_plus_three = eval two_plus_three := by rfl

eval' two_plus_three

=>

eval' (plus (const 2) (const 3))

=>

eval_acc (plus (const 2) (const 3)) 0

=>

eval_acc (const 3) (eval_acc (const 2) 0)

=>

eval_acc (const 3) ( 2 + 0)

=>

eval_acc (const 3) 2

=>

3 + 2

=>

5

QUIZ: Is eval_acc tail recursive?

Lets try to prove that eval' and eval are "equivalent".

Can you figure out a suitable helper lemma that would let us complete

the proof of eval_eq_eval'?

theorem magic_theorem : ∀ e res, eval_acc e res = eval e + res := by

intros e res

induction e generalizing res

. case const n => rfl

. case plus e1 e2 ih1 ih2 =>

simp_arith [eval, eval_acc, ih1, ih2]

theorem eval_eq_eval' : ∀ e, eval e = eval' e := by

intros e

simp [eval', magic_theorem]

Trick 4: Functional Induction

Based on Joachim Breitner's notes on Functional Induction

def len (xs: List α) : Nat :=

match xs with

| [] => 0

| _::xs' => 1 + len xs'

def alt (xs ys : List α) : List α :=

match xs, ys with

| [], ys => ys

| xs, [] => xs

| x::xs', y::ys' => x :: y :: alt xs' ys'

#eval alt [1,2,3,4] [10]

First, lets try a "brute force" proof.

exp ::= const c | var | plus exp exp | mult exp exp

(plus

(mult

(const 7)

(mult (var (mult var var)))))

(plus

(mult (const 2) (mult var var))

(const 10))

)

7x^3 + 2*x^2 + 10

5x^3 + 12*x^2

[7, 2, 0, 10]

[5, 12, 0, 0]

[12, 14, 0, 10]

theorem alt_len_easy : ∀ {α : Type} (xs ys : List α),

len (alt xs ys) = len xs + len ys := by

intros α xs ys

induction xs, ys using alt.induct

. case case1 => simp [alt, len]

. case case2 => simp [alt, len]

. case case3 x xs' y ys' ih => simp_arith [alt, len, *]

theorem alt_len : ∀ {α : Type} (xs ys : List α),

len (alt xs ys) = len xs + len ys := by

intros α xs ys

induction xs

. case nil =>

simp [alt, len]

. case cons x xs' ih_xs =>

induction ys

. case nil =>

simp [alt, len]

. case cons y ys' ih_ys =>

simp [alt, len, *]

sorry

Instead, it can be easier to do the same induction as mirrors the recursion in alt

theorem alt_len' : ∀ {α : Type} (xs ys : List α), len (alt xs ys) = len xs + len ys := by

intros α xs ys

induction xs, ys using alt.induct

. case case1 => simp [alt, len]

. case case2 => simp [alt, len]

. case case3 => simp_arith [alt, len, *]

set_option pp.fieldNotation false

Expressions

This material is based on

- Chapter 3 of Concrete Semantics

Arithmetic Expressions

abbrev Val := Nat

abbrev Vname := String

inductive Aexp where

| num : Val -> Aexp

| var : Vname -> Aexp

| add : Aexp -> Aexp -> Aexp

deriving Repr

open Aexp

def aexp_5 := num 5

def aexp_x := var "x"

def aexp_x_plus_y := add (var "x") (var "y")

def aexp_2_plus_z_plus_3 := add (num 2) (add (var "z") (num 3))

States

abbrev State := Vname -> Val

-- initial state

def st0 : State := λ _ => 0

-- update state

def upd (s: State) (x: Vname) (v: Val) : State :=

λ y => if y = x then v else s y

def st0' := upd st0 "x" 100

notation:10 st " [ " x " := " v " ] " => upd st x v

def st0'' := st0 [ "x" := 100 ] [ "y" := 99 ] [ "z" := 666 ]

#eval st0'' "z"

Evaluation

def aval (a: Aexp) (s: State) : Val :=

match a with

| num n => n

| var x => s x

| add a1 a2 => aval a1 s + aval a2 s

def st1 := st0 ["x" := 2] [ "y" := 10 ] [ "z" := 100 ]

example : aval aexp_5 st0 = 5 := rfl

example : aval aexp_x st0 = 0 := rfl

example : aval aexp_x_plus_y st1 = 12 := rfl

example : aval aexp_2_plus_z_plus_3 st1 = 105 := rfl

Constant Folding

Compilers often want to "simplify" expressions by performing, at compile time, various operations on constants.

For example, we may want to simplify an expression

add (var "x") (add (num 3) (num 1))

to just

add (var "x") (num 4)

We can implement this idea in a little recursive funciton asimp_const

that does this form of constant folding in a bottom-up manner

def asimp_const (a: Aexp) : Aexp :=

match a with

| num n => num n

| var x => var x

| add a1 a2 => match asimp_const a1, asimp_const a2 with

| num n1, num n2 => num (n1 + n2)

| a1', a2' => add a1' a2'

Equivalence of Constant Folding

Lets prove that asimp_const does not change the meaning of the expression a.

theorem aval_asimp_const : ∀ a s, aval a s = aval (asimp_const a) s := by

sorry

TACTIC: simp_all to simplify hypotheses

Lets flip the order of the equality.

-- REWRITING hypotheses: simp_all

theorem aval_asimp_const' : ∀ a s, aval (asimp_const a) s = aval a s := by

sorry

Oh no! The exact same proof does not work! lean is stuck at the goal

s : State

a✝¹ a✝ : Aexp

n1✝ n2✝ : Val

x✝¹ : asimp_const a✝ = num n2✝

x✝ : asimp_const a✝¹ = num n1✝

ih2✝ : aval (asimp_const a✝¹) s = aval a✝¹ s

ih1✝ : aval (asimp_const a✝) s = aval a✝ s

⊢ n1✝ + n2✝ = aval a✝¹ s + aval a✝ s

Here, we have the hypotheses of the IH,

ih2✝ : aval (asimp_const a✝¹) s = aval a✝¹ sih1✝ : aval (asimp_const a✝) s = aval a✝ s

and separately we know that

... : asimp_const a✝ = num n2✝... : asimp_const a✝¹ = num n1✝

So what we want is to apply the above "knowledge" to rewrite the ih1✝ and ih2✝, which is

achieved by the tactic simp_all; which then makes the proof go through.

Extended Folding with a Smart Constructor

Lets extend the constant folding so that additions-by-zero are dropped,

i.e. add (num 0) a or add a (num 0) just become a.

A clean way to do so is by writing a smart constructor plus which handles

both the num-num-addition and the zero-addition cases as

def plus (a1 a2: Aexp) : Aexp :=

match a1, a2 with

| num n1, num n2 => num (n1 + n2)

| num n , a => if n = 0 then a else add (num n) a

| a, num n => if n = 0 then a else add a (num n)

| _, _ => add a1 a2

We can now write a general simplifier asimp that recursively

traverses the Aexp and invokes plus at each add

def asimp (a: Aexp) : Aexp :=

match a with

| num n => num n

| var x => var x

| add a1 a2 => plus (asimp a1) (asimp a2)

Lets try to prove that asimp does not change the meaning of an expression.

theorem aval_asimp_stuck : ∀ a s, aval a s = aval (asimp a) s := by

intros a s

induction a <;> simp [asimp, aval, *]

sorry

Oof. The "direct" proof-by-induction is stuck. Can you think of a suitable "helper lemma"?

Yikes, we're stuck with a goal that looks like

⊢ aval (asimp a✝¹) s + aval (asimp a✝) s = aval (plus (asimp a✝¹) (asimp a✝)) s

We need a helper lemma that might tell us what aval (plus a1 a2) s should evaluate to?

theorem aval_aplus' : ∀ a1 a2 s, aval (plus a1 a2) s = aval a1 s + aval a2 s := by

intros a1 a2 s

cases a1 <;> cases a2 <;> simp_arith [aval, plus] <;> sorry

The split tactic

Hmm, now we're left with a goal that looks like

s : State

a✝¹ : Val

a✝ : Vname

⊢ aval (if a✝¹ = 0 then var a✝ else add (num a✝¹) (var a✝)) s = a✝¹ + s a✝

We need to "split-cases" on the if a✝¹ = 0 branch ... convenient to do so with split

(and then keep simp-ing!)

theorem aval_plus: ∀ a1 a2 s, aval (plus a1 a2) s = aval a1 s + aval a2 s := by

intros a1 a2

sorry

We can use this helper to complete the proof

theorem aval_asimp : ∀ a s, aval a s = aval (asimp a) s := by

intros a s

induction a <;> simp [asimp, aval, aval_plus, *]

Boolean Expressions

Lets define a datatype for boolean expressions

inductive Bexp where

| bbool : Bool -> Bexp

| bnot : Bexp -> Bexp

| band : Bexp -> Bexp -> Bexp

| bless : Aexp -> Aexp -> Bexp

deriving Repr

open Bexp

Boolean Evaluator

def bval (b: Bexp) (s: State) : Bool :=

match b with

| bbool v => v

| bnot b' => !bval b' s

| band b1 b2 => bval b1 s && bval b2 s

| bless a1 a2 => aval a1 s < aval a2 s

"Smart Constructors" for Boolean Constant Folding

def smart_and (b1 b2: Bexp) : Bexp :=

match b1, b2 with

| bbool true, _ => b2

| bbool false, _ => bbool false

| _, bbool true => b1

| _, bbool false => bbool false

| _, _ => band b1 b2

def smart_not (b: Bexp) : Bexp :=

match b with

| bbool true => bbool false

| bbool false => bbool true

| _ => bnot b

def smart_less (a1 a2: Aexp) : Bexp :=

match a1, a2 with

| num n1, num n2 => bbool (n1 < n2)

| _, _ => bless a1 a2

def bsimp (b: Bexp) : Bexp :=

match b with

| bbool v => bbool v

| bnot b => smart_not (bsimp b)

| band b1 b2 => smart_and (bsimp b1) (bsimp b2)

| bless a1 a2 => smart_less (asimp a1) (asimp a2)

Smart Constructors are Equivalent

theorem smart_not_eq : ∀ b s, bval (smart_not b) s = bval (bnot b) s := by

intros b s

cases b

. case bbool v => cases v <;> rfl

. case bnot => rfl

. case band => rfl

. case bless => rfl

theorem smart_and_eq : ∀ b1 b2 s,

bval (smart_and b1 b2) s = bval (band b1 b2) s := by

intros b1 b2 s

cases b1 <;> cases b2 <;> simp_all [smart_and, bval] <;> split <;> simp_all [bval]

theorem smart_less_eq : ∀ a1 a2 s, bval (smart_less a1 a2) s = bval (bless a1 a2) s := by

intros a1 a2 s

cases a1 <;> cases a2 <;> simp_all [smart_less, bval, aval]

Correctness of Boolean Simplification

Lets prove that bval_bsimp b does not

change the meaning of an expression b.

theorem bval_bsimp_stuck : ∀ b s, bval b s = bval (bsimp b) s := by

intros b s

sorry

Backwards Rewriting / Simplification

Boo! We cannot use aval_asimp directly.

The simp uses a theorem of the form lhs = rhs

to rewrite occurrences of lhs with rhs.

In this case, however,

-

the theorem

aval_asimpsaysaval a s = aval (asimp a) s -

but the goal contains a term

aval (asimp a') s -

where we want to rewrite the RHS of the theorem with the LHS!

You can do this either by

-

making a new theorem where the LHS and RHS are flipped (which is a bit silly...)

-

or instead by specifying

<-in thesimptactic.

theorem bval_bsimp : ∀ b s, bval b s = bval (bsimp b) s := by

intros b s

sorry

Case Study: Compiling to a Stack Machine

In this case study, we will define a "stack machine" that operates on a stack of values.

Intuition

Given an a : Aexp , say

((x + 10) + (5 + y))

We will compile it into a sequence of "instructions" that operate on a stack.

LOAD x

LOADI 10

ADD

LOADI 5

LOAD y

ADD

ADD

Lets execute this sequence of instructions on a state s defined as [x |-> 100, y |-> 200] as

[]

--> LOAD x

[100]

--> LOADI 10

[10, 100]

--> ADD

[110]

--> LOADI 5

[5, 110]

--> LOAD y

[200, 5, 110]

--> ADD

[205, 110]

--> ADD

[315]

Note that the final result left on the stack is 315 which is exactly what aval a s would return.

Let's define a "compiler" and "exec" function and prove that the compiler is correct!

Stack Machine: Instructions

inductive Instr where

| LOADI : Val -> Instr

| LOAD : Vname -> Instr

| ADD : Instr

deriving Repr

open Instr

Stack Machine: Interpreter

A Stack is just a list of values

abbrev Stack := List Val

Here's a function exec1 that executes a single instruction

def exec1 (s:State) (i:Instr) (stk:Stack) : Stack :=

match i, stk with

| LOADI n, _ => (n :: stk)

| LOAD x, _ => (s x :: stk)

| ADD , n::m::stk => (m + n) :: stk

| ADD , _ => []

Here's a function exec that executes a sequence of instructions by invoking exec1 on each instruction.

def exec (s:State) (is: List Instr) (stk:Stack) : Stack :=

match is with

| [] => stk

| i::is' => exec s is' (exec1 s i stk)

Stack Machine: Compiler

Here's a function that "compiles" an Aexp into a List Instr

def comp (a: Aexp) : List Instr :=

match a with

| num n => [LOADI n]

| var x => [LOAD x]

| add a1 a2 => comp a1 ++ comp a2 ++ [ADD]

Proving Compiler Correctness

theorem comp_exec_stuck : ∀ {s : State} {a : Aexp} { stk : Stack },

exec s (comp a) stk = aval a s :: stk := by

intro s a stk

induction a generalizing s stk

case num n => rfl

case var x => rfl

case add a1 a2 ih1 ih2 => simp_all [comp, aval, exec, exec1]; sorry

Oh no! We're stuck, what helper lemma do we need?

theorem comp_exec : ∀ {s : State} {a : Aexp} { stk : Stack },

exec s (comp a) stk = aval a s :: stk := by

intro s a stk

induction a generalizing s stk

case num n => rfl

case var x => rfl

sorry

set_option pp.fieldNotation false

Evidence

This material is based on

- Chapter 3 of Concrete Semantics

- Inductive Propositions from Software Foundations

The Collatz Conjecture

Per Wikipedia, the Collatz Conjecture is

one of the most famous unsolved problems in mathematics. The conjecture asks whether repeating two simple arithmetic operations will eventually transform every positive integer into 1... It concerns sequences of integers where each term is obtained from the previous term as follows:

- if a term is even, the next term is one half of it.

- if a term is odd, the next term is 3 times the previous term plus 1.

The conjecture is that these sequences always reach 1, no matter which positive integer is chosen to start the sequence.

The conjecture has been shown to hold for all positive integers up to $$2.95 \times 10^{20}$$, but no general proof has been found.

Lets try to model the Collatz Conjecture in Lean.

A function that computes the half of a Nat and that determines if a Nat is even.

def half (n : Nat) : Nat :=

match n with

| 0 => 0

| 1 => 0

| ((n + 1) + 1) => (half n) + 1

example : half 5 = 2 := by rfl

example : half 10 = 5 := by rfl

def even (n: Nat) : Bool :=

match n with

| 0 => true

| 1 => false

| (n + 1) + 1 => even n

example : even 5 = false := by rfl

example : even 10 = true := by rfl

Now, lets try to write a function that computes the next term in the Collatz sequence, and use it to run the Collatz sequence starting from a given number.

def collatz_step (n : Nat) : Nat :=

if even n then half n else 3 * n + 1

def run_collatz (steps n : Nat) : List Nat :=

match steps with

| 0 => [n]

| steps + 1 => n :: run_collatz steps (collatz_step n)

Lets try to run_collatz for a few numbers...

#eval run_collatz 5 5

#eval run_collatz 17 15

#eval run_collatz 26 200

The Termination Restriction

Can we write a function to count the number of steps needed to reach 1?

-- def collatz_steps (n : Nat) : Nat :=

-- match n with

-- | 1 => 1

-- | n => collatz_steps (collatz_step n) + 1

Welp! lean is unhappy with this definition as it cannot determine the function terminates!

All our previous examples, lean was fine with because the "recursion" was on "smallar inputs, e.g.

in plus below, in each recursive call, n is getting smaller -- we start with n+1 and recurse on n

all the way till it reaches 0, so lean is happy. If you have (possibly) non-terminating functions, you can

prove things like 1 = 2 which would make the whole system inconsistent (i.e. useless).

def plus (n m : Nat) : Nat :=

match n with

| 0 => m

| n + 1 => (plus n m) + 1

So: lean and similar provers require that all recursive functions are provably terminating.

How can we then even specify the Collatz Conjecture in lean ?

Idea: Inductively Defined Evidence (or Proofs)

We can specify the collatz conjecture by defining a way to explicitly

construct evidence that a given number n will eventually reach

1 in the Collatz sequence.

For example, we know that the number n reaches 1 in the Collatz sequence if

- [ collatz-one ] if

nis equal to1, OR - [ collatz-evn ] if

nis even andhalf nreaches1, OR - [ collatz-odd ] if

nis not even and3*n + 1reaches1

We can define a datatype whose values represent the above conditions.

In PL, we often write the above three rules as follows, where the

- "numerator" is the conditions or hypotheses under which the rule holds

- "denominator" is the conclusion or consequence that follows from the conditions.

--------------------- [collatz-one]

collatz_reaches_one 1

even n collatz_reaches_one (half n)

---------------------------------------- [collatz-even]

collatz_reaches_one n

¬ (even n) collatz_reaches_one (3*n + 1)

----------------------------------------- [collatz-odd]

collatz_reaches n

Inductive Propositions

We can encode the above rules in lean as an inductive proposition

inductive collatz_reaches_one : Nat -> Prop where

| collatz_one : collatz_reaches_one 1

| collatz_evn : ∀ {n : Nat}, even n -> collatz_reaches_one (half n) -> collatz_reaches_one n

| collatz_odd : ∀ {n : Nat}, ¬ even n -> collatz_reaches_one (3*n + 1) -> collatz_reaches_one n

open collatz_reaches_one

Note that the above is a rather fancy data type, where, unlike List or Nat

- the constructed "type" is

Propi.e. a proposition, and - the actual

Propis different for the different constructors!

So, in

-

The

onecase: the termcollatz_oneis an object of typecollatz_reaches_one 1 -

The

evncase: the constructorcollatz_evntakes as input two arguments,- a proof that

nis even and - a proof that

half nreaches1, and constructs a proof thatnreaches1

- a proof that

-

The

oddcase: the constructorcollatz_oddtakes as input two arguments,- a proof that

nis not even and - a proof that

3*n + 1reaches1, and constructs a proof thatnreaches1

- a proof that

As an example, we can construct evidence that 5 reaches 1 in the Collatz sequence

def collatz_1 : collatz_reaches_one 1 :=

collatz_one

def collatz_2 : collatz_reaches_one 2 :=

let even_2 : even 2 := by simp [even]

collatz_evn even_2 (collatz_1)

def collatz_4 : collatz_reaches_one 4 :=

let even_4 : even 4 := by simp [even]

collatz_evn even_4 (collatz_2)

def collatz_8 : collatz_reaches_one 8 :=

let even_8 : even 8 := by simp [even]

collatz_evn even_8 (collatz_4)

def collatz_16 : collatz_reaches_one 16 :=

let even_16 : even 16 := by simp [even]

collatz_evn even_16 (collatz_8)

def collatz_5 : collatz_reaches_one 5 :=

let odd_5 : ¬ (even 5) := by simp [even]

collatz_odd odd_5 (collatz_16)

You can also construct evidence with tactics ...

theorem collatz_5_tt : collatz_reaches_one 5 := by

apply collatz_odd

simp [even]

apply collatz_evn

simp [even]

simp [half]

apply collatz_evn

simp [even]

simp [half]

apply collatz_evn

simp [even]

simp [half]

apply collatz_evn

simp [even]

simp [half]

apply collatz_one

Finally, you can state the Collatz conjecture as follows:

theorem collatz_theorem : ∀ n, collatz_reaches_one n := by

sorry -- *well* out of the scope of CSE 230 ...

Now that we have motivated the need for explicit evidence, lets look at some more examples.

Example: Even Numbers

Lets try to define the notion of a number n being even as an inductive proposition ev n.

What are the rules for a number n to be even?

Lets try to write these rules down in lean...

inductive ev : Nat -> Prop where

| evZ : ev 0

| evSS : ∀ {n: Nat}, ev n -> ev (n + 2)

open ev

As before, we can construct explicit evidence for a few numbers...

def even_0 : ev 0 := evZ

def even_2 : ev 2 := evSS evZ

def even_4 : ev 4 := evSS (evSS evZ)

def even_6 : ev 6 := evSS (evSS (evSS evZ))

Note that evidence is literally just a value so we can use even_4 to get a proof of even_6

def even_6' : ev 6 := evSS ( even_4 )

Tactic: apply

Building up these "trees" can quickly get tiring. Tactics help! The apply constructor

takes the current goal and "applies" a constructor to it, thus reducing the goal to its

"hypotheses".

def even_8 : ev 8 := by

apply evSS

apply evSS

apply evSS

apply evSS

apply evZ

Tactic: constructor

The constructor tactic can let you skip the name of the actual constructor,

as long as there is a particular constructor that matches the current goal.

(Of course, in the below you can also repeat the application of constructor).

def even_8' : ev 8 := by

constructor

constructor

constructor

constructor

constructor

Tactic: solve_by_elim

The solve_by_elim tactic is even funner: it can do a bit of "search" by recursively apply-ing

the appropriate constructors (upto some fixed search depth.)

def even_8'' : ev 8 := by

solve_by_elim

Constructing / Producing Evidence

Lets try to prove that if even n returns true,

then we can construct evidence that ev n.

theorem even_ev : ∀ {n : Nat}, even n = true -> ev n := by

intros n h

induction n using even.induct case case1 => constructor case case2 => contradiction case case3 n' ih' => simp_all [even]; constructor; assumption

Destructing / Using Evidence

Next, lets try to prove the opposite: whenever

we have evidence that ev n, we can prove that

even n = true!

How can we possibly prove this?

theorem ev_even : ∀ {n : Nat}, ev n -> even n = true := by

intros n h induction h case evZ => rfl case evSS => simp [even, *]

Example: Reflexive, Transitive Closure

Suppose we have a datatype to represent some set of persons

inductive person : Type where

| alice : person

| bob : person

| charlie : person

| diane : person

| esther : person

| fred : person

| gerald : person

| harry : person

open person

we can define a relation parent_of that specifies some relationship between two persons.

inductive parent_of : person -> person -> Prop where

| parent_ab : parent_of alice bob

| parent_bc : parent_of bob charlie

| parent_cd : parent_of charlie diane

| parent_ef : parent_of esther fred

| parent_fg : parent_of fred gerald

| parent_gh : parent_of gerald fred

open parent_of

inductive anc_of : person -> person -> Prop where

| anc_self : ∀ {x}, anc_of x x

| anc_step : ∀ {x y z}, parent_of x y -> anc_of y z -> anc_of x z

open anc_of

example : anc_of alice diane := by

repeat constructor

theorem anc_of_transitive : ∀ {a b c},

anc_of a b -> anc_of b c -> anc_of a c

:= by

intros a b c anc_ab anc_bc

induction anc_ab

. case anc_self =>

assumption

. case anc_step =>

rename_i a x b _ _ ih

simp_all []

constructor

assumption

assumption

Now suppose we want to define an ancestor_of relationship, as

---------------- [anc-self] anc_of x x

parent_of x y anc_of y z ----------------------------- [anc-step] anc_of x z

- (reflexive)

xis anancestor_ofx` or - (transitive) if

parent_of x yandancestor_of y zthenancestor_of x z

That is, the ancestor_of relation is the reflexive and transitive

closure of a relation parent_of.

Suppose that r is a binary relation on α i.e. some fact that holds on two α.

The reflexive transitive closure of r is defined as the relation rr where

- (reflexive)

rr x xi.e.rrrelates every elementxto itself, - (transitive) if

r x yandrr y zthenrr x z

Lets define this as an inductive proposition

inductive star {α : Type} (r: α -> α -> Prop) : α -> α -> Prop where

| refl : ∀ {a : α}, star r a a

| step : ∀ {x y z : α}, r x y -> star r y z -> star r x z

open star

We can now define ancestor_of using star, and then test it out on a few examples.

abbrev ancestor_of := star parent_of

example : ancestor_of alice alice := by

sorry

example : ancestor_of alice diane := by

sorry

example : ancestor_of esther fred := by

sorry

If you think about it, if

- if

ais anancestor_ofsome personb, - and

bis anancestor_ofsome personc

then

ashould also be anancestor_ofc` ?

In fact, this transitivity fact should hold for any star r. Lets try to prove it!

HINT: The solve_by_elim tactic is quite handy.

theorem star_one : ∀ { α : Type} { r: α -> α -> Prop} {a b : α},

r a b -> star r a b

:= by

intros α r a b r_ab

apply step r_ab

apply refl

theorem star_trans : ∀ {α : Type} {r : α -> α -> Prop} {a b c : α},

star r a b -> star r b c -> star r a c

:= by

intros α r a b c r_ab r_bc

induction r_ab

. case refl =>

assumption

. case step =>

simp_all []

constructor

assumption

assumption

Example: Grammars and Parsing

Lets look at one last example of doing induction on evidence. Consider two grammars

for parsing strings over the characters a and b

The first grammar is defined by the non-terminal S

(((((((((((((())))))))))))))(((((())))))

S ::= ε | a S b | S S

The second grammar is defined by the non-terminal T

T ::= ε | T a T b

Do these grammars accept the same set of strings?

inductive Alphabet where

| a : Alphabet

| b : Alphabet

deriving Repr

open Alphabet

inductive gS : List Alphabet -> Prop where

| gS0 : gS []

| gS1 : ∀ {s : List Alphabet}, gS s -> gS (a :: s ++ [b])

| gS2 : ∀ {s1 s2 : List Alphabet}, gS s1 -> gS s2 -> gS (s1 ++ s2)

open gS

inductive gT : List Alphabet -> Prop where

| gT0 : gT []

| gT1 : ∀ {t1 t2 : List Alphabet}, gT t1 -> gT t2 -> gT (t1 ++ ([a] ++ t2 ++ [b]))

open gT

Exercise: Try to prove that the two grammars are equivalent,

that is complete the proofs of S_imp_T and T_imp_S below.

(Start with T_imp_S)

theorem T_append : ∀ {s1 s2 : List Alphabet}, gT s1 -> gT s2 -> gT (s1 ++ s2) := by intros s1 s2 T_s1 T_s2 induction T_s2 case gT0 => simp [List.append_nil]; assumption case gT1 t1' t2' _ _ _ _ => have h : (s1 ++ (t1' ++ ([a] ++ t2' ++ [b]))) = (s1 ++ t1' ++ ([a] ++ t2' ++ [b])) := by simp [List.append_assoc] rw [h] constructor assumption assumption

theorem S_imp_T : ∀ {w : List Alphabet}, gS w -> gT w := by

intros _ gs induction gs case gS0 => constructor case gS1 => apply (gT1 gT0); assumption case gS2 _ s1 s2 _ _ T_s1 T_s2 => apply T_append <;> assumption

theorem T_imp_S : ∀ {w : List Alphabet}, gT w -> gS w := by

intros _ gt induction gt case gT0 => constructor case gT1 => constructor . case _ => simp_all [] -- assumption . case _ => constructor simp_all [List.append]

theorem S_equiv_T : ∀ {w : List Alphabet}, gS w ↔ gT w := by

intros w

constructor

apply S_imp_T

apply T_imp_S

import Cse230wi25.BigStep

set_option pp.fieldNotation false

set_option pp.proofs true

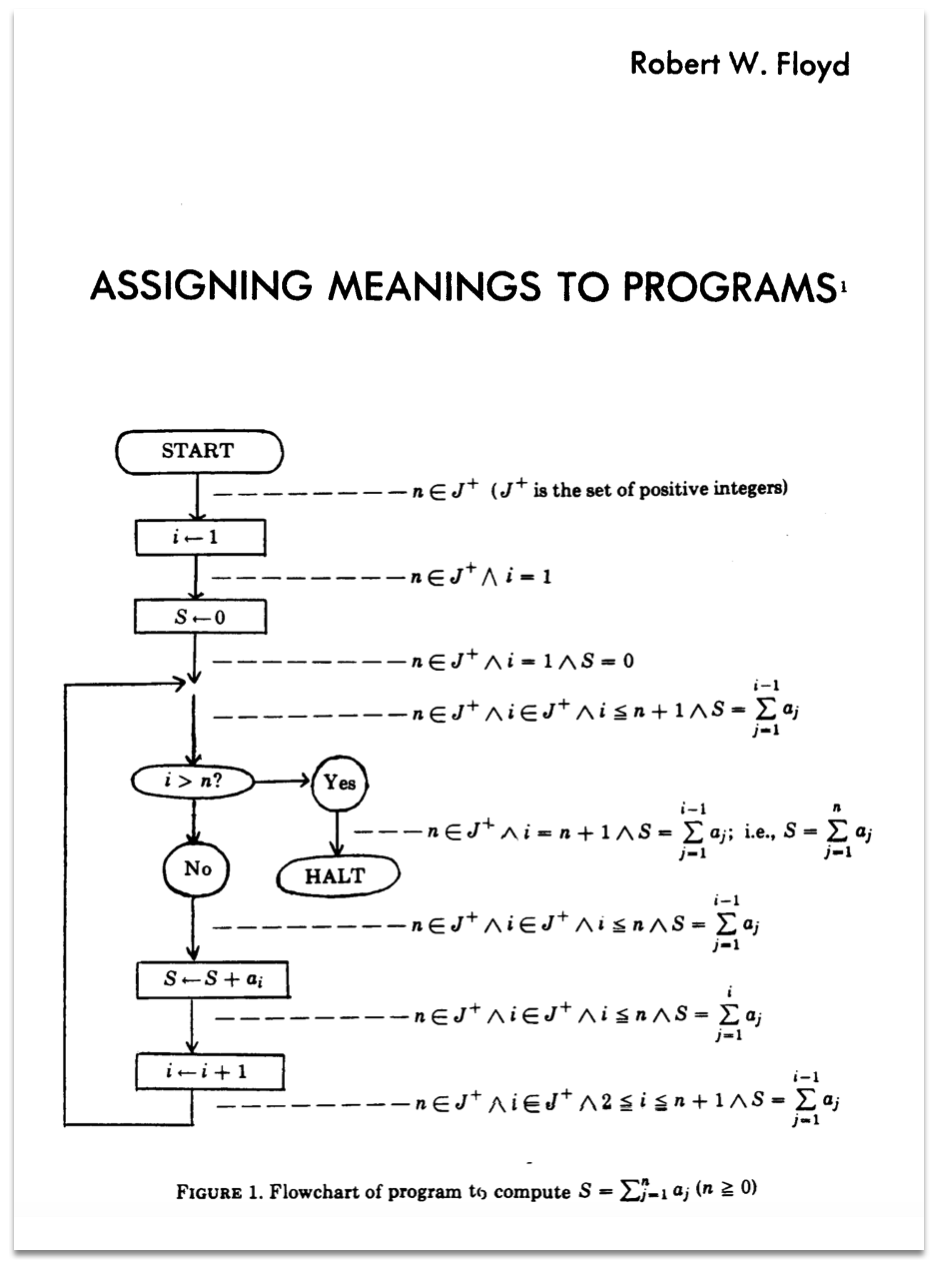

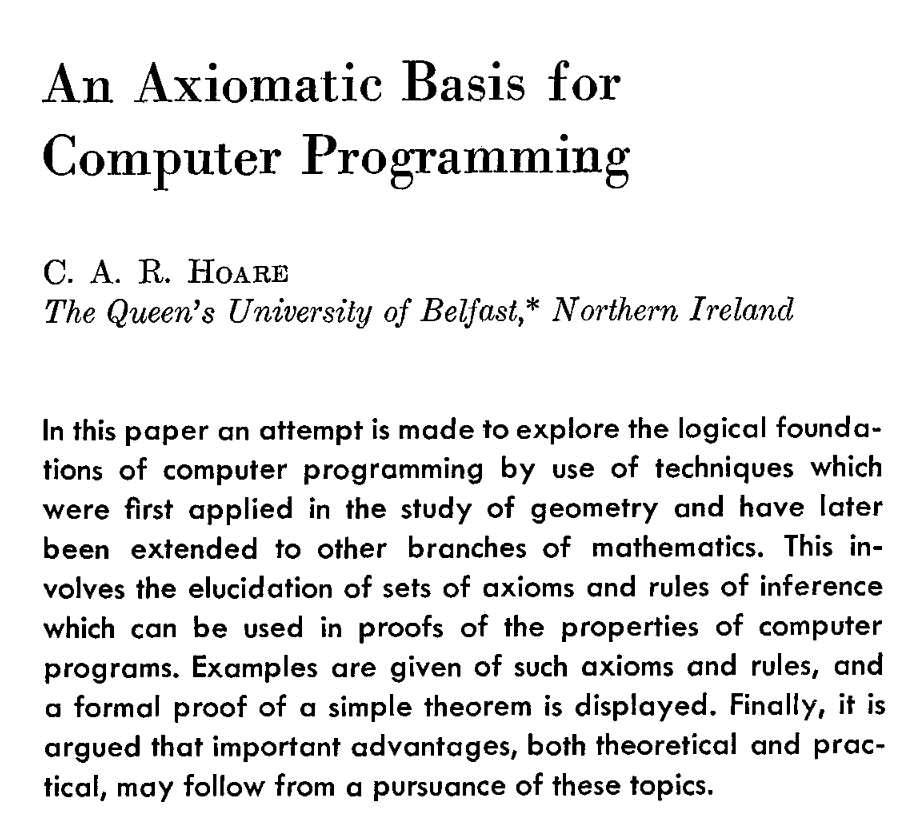

Axiomatic Semantics

The BigStep semantics that was saw previously was helpful in proving properties

about groups of programs, for example, that

- that every command

cwas deterministic or - that every command

cwas equivalent toSKIP ;; corIF cond THEN c ELSE cor - that every command

x <~ a;; y <~ awas equivalent tox <~ a;; y <~ x(ifxwas not read ina).

Next, lets try to use the BigStep semantics to check properties of individual programs.

Example: Swapping two Variables

Consider the following Com program that swaps

the values of x and y using z as a temporary

storage.

open Aexp

def swap :=

-- {{ y = b /\ x = a }}

z <~ var x ;;

-- {{ y = b /\ z = a }}

x <~ var y ;;

-- {{ x = b /\ z = a }}

y <~ var z

-- {{ x = b /\ y = a }}

theorem swap_ok : ∀ {s t a b},

(⟨ swap , s ⟩ ==> t) ->

(s x = a /\ s y = b) ->

(t x = b /\ t y = a) := by

intros s t a b swap_s_t xa_yb

simp_all [swap]

cases xa_yb; rename_i xa yb

cases swap_s_t

rename_i swap_1 swap_23

cases swap_23

rename_i swap_2 swap_3

cases swap_1

cases swap_2

cases swap_3

simp [aval, upd, *]

Lets try to prove that swap indeed correctly swaps the values of x and y.

How can we specify this correctness property as a theorem?

How can we prove that theorem?

theorem swap_swaps : ∀ {s t : State} {n m : Val},

s x = n -> s y = m -> (⟨ swap, s ⟩ ==> t) -> (t x = m) /\ (t y = n) := by

sorry

Instead of the cases we can prove a theorem that precisely characterizes what the "shape"

of output state of an assignment is:

-- @[simp]

theorem assign_step : ∀ {x a s t}, (⟨ x <~ a, s ⟩ ==> t) <-> (t = (s [x := aval a s])) := by

intros x a s t

apply Iff.intro

. case mp => intros xs; cases xs ; trivial

. case mpr => intros; simp_all [] ; apply BigStep.Assign

And now, we can tell lean to use that assign_step to "fill in" the intermediate

s1, s2 and s3 to complete the proof.

theorem swap_swaps' : ∀ {s t : State} {n m : Val},

s x = n -> s y = m -> (⟨ swap, s ⟩ ==> t) -> (t x = m) /\ (t y = n) := by

intros s t n m sxn sym swap_123

simp_all [swap]

cases swap_123; rename_i s1 swap_1 swap_23

cases swap_23; rename_i s2 swap_2 swap_3

simp_all [assign_step, aval, upd]

Well, that wasn't too bad. But lets try a more interesting example:.

Example: Summing the numbers from 0..n

Consider the following loop which sums up the values of the numbers from 0 to x

∀ {start finish a}, ⟨ sum_com, start ⟩ ==> finish -> start x = a -> finish y = sumTo a

start x = a finish y = sumTo a

def sumTo (n: Nat) : Nat :=

match n with

| 0 => 0

| n' + 1 => n' + sumTo n'

def sum_com : Com :=

-- {{ x = a }}

y <~ 0 ;;

-- {{ x = a /\ y = 0 }}

WHILE

-- {{ x <= a }}

0 << x

DO

-- {{ x <= a /\ 0 < x }}

y <~ y + x ;;

x <~ x - 1

END

-- {{ y = sum a }}

-- x = a, y = 0

-- x = a-1, y=a

-- x = a-2, y=a + a -1

-- x = a-3, y=a + a - 1 + a - 2

-- x = 0 , y= a + a-1 + a-2 + ... + 1

-- y = 1 + 2 + 3 + ... + a

How can we specify that this correctly sums up the numbers 0 + ... + n ?

def sum (n:Nat) : Nat :=

match n with

| 0 => 0

| n' + 1 => n + sum n'

-- A program! ------------------------------------------------------------

abbrev csum := y <~ y + x ;; x <~ x - 1

abbrev wsum := WHILE 0 << x DO csum END

abbrev imp_sum := "y" <~ 0 ;; wsum

theorem wsum_sum' : (⟨ wsum, s ⟩ ==> t) -> ((t "y") = s "y" + sum (s "x")) := by

sorry

-- intro wsum_s_t

-- generalize h : wsum = ws at wsum_s_t -- LEAN:ANF BUG

-- induction wsum_s_t <;> simp_all [wsum]

-- . case WhileFalse =>

-- cases h

-- rename_i c _ s bfalse left _

-- simp [<-left] at bfalse

-- simp_all [bval, aval, sum]

-- . case WhileTrue =>

-- cases h

-- rename_i b c s s1 t btrue c_s_s1 w_s1_t left right

-- simp [<-left] at btrue

-- sorry

theorem csum_sum : (⟨ csum, s ⟩ ==> t) -> ( (t "x" = s "x" - 1) /\ (t "y") = s "y" + s "x")

:= by

intros cs; cases cs; rename_i s1 st1 st2; simp_all [assign_step]

by_cases (x=y) <;> (simp_all [upd, aval]; try intros; contradiction)

theorem wsum_sum : (⟨ wsum, s ⟩ ==> t) -> ((t "y") = s "y" + sum (s "x")) := by

intros wsums

generalize h : wsum = ws at wsums -- LEAN:ANF BUG

induction wsums <;> try simp_all []

.case WhileFalse =>

cases h

rename_i b c s bfalse cond _

have x_eq_0 : s "x" = 0 := by

simp [<-cond, bval, aval] at bfalse

assumption

simp_all [sum]

.case WhileTrue =>

rename_i b csum s s1 s2 btrue c_step _ _ _

cases h

rename_i cond hr

have s1xy : s1 "x" = s "x" - 1 /\ s1 "y" = s "y" + s "x" := by

apply csum_sum; simp_all []

cases s1xy

have sum_x : sum (s "x") = s "x" + sum (s "x" - 1) := by

simp [<-cond, bval, aval] at btrue

generalize hx : s "x" = sx

cases sx <;> simp_all [sum]

simp_all [Nat.add_assoc]

theorem while_sum : (⟨ imp_sum, s ⟩ ==> t) -> t "y" = sum (s "x") := by

intros ws

cases ws

rename_i y0_step ws_step

cases y0_step

generalize h : upd s y (aval 0 s) = s0 at ws_step